WiFi-tracking is used for many purposes, including producing heat-maps of spaces, counting passers-by and analyzing people movement and visits. This can be extremely useful for businesses to better understand the use of their space and how to optimize this, and it is already in wide use in shopping malls, airports and hotels all around the world.

About WIFI-tracking

WiFi-tracking technology relies on devices such as smart phones sending so called probe requests. With enabled wireless network, a device will broadcast a probe in regular intervals to see which known or unknown wireless networks are available to possibly connect to. By capturing these requests along with some other information such as signal strength and time, a fairly accurate analysis of the location and behavior can be made. By combining data from different access points in close vicinity, an accurate location can be determined through trilateration.

The GDPR as introduced on May 25th 2018, does make this practice harder: as MAC (Media Access Control) addresses are considered (pseudonymised) personal data, e.g. it can be used to single out a person, it requires a valid legal base and adherence to the other articles of GDPR. This article explores the possibilities for meeting these requirements.

Personal data and scope of the GDPR

The definition of personal data under the GDPR is outlined in Article 4(1):

‘personal data’ means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (‘data subject’); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person;

On 19 October 2016, the Court of Justice of the European Union (the “CJEU”) published its judgment in Case 582/14 – Patrick Breyer v Germany. This judgement concludes that dynamic IP addresses are to be seen as personal data, and following the same logic, MAC addresses of personal devices are therefore certainly to be seen as personal data.

While alternatives for MAC addresses, such as hashed or encrypted versions, can be stored and processed, these would still be considered pseudonymous if they can uniquely single out a single device belonging to a natural person. Pseudonymising data does not move it out of scope of the GDPR as the data can still be linked back to a natural person, with the use of extra information.

As soon as position of devices is determined, there is location data available as well which certainly falls under the GDPR.

Once data is truly anonymized (e.g. aggregated data with a significant enough sample size), and it can no longer be related back to a single data subject, it will be out of scope of the GDPR and can be further used. Nevertheless a valid legal base will be required for the initial collection of any personal data.

Who is the controller?

Defining the different stakeholders is important to further analyze the GDPR compliance. The data subject within WiFi-tracking is the person with a personal, WiFi-enabled device that is being tracked. This person should be guaranteed GDPR compliant processing of his or her personal data. That includes the requirement of properly informing them about their data being processed their rights under the GDPR.

Defining the data controller and data processor is more challenging. The GDPR has defined that the controller is the one ‘determining the means and purpose for processing’ and the processor as the one ‘processing data on behalf of the controller, based on specific written instructions’. In a WiFi-tracking situation this may mean different things based on the specifics of the setup.

If a venue utilizes WiFi-tracking for its own purposes (such as capacity planning) with its own hardware using a third party software, it is quite likely that the venue is the controller, and the third party software provider the processor. This also requires a data processing agreement to be in place between the two to ensure the processor is given specific written instructions for processing.

In case the hardware is placed in the venue by a third party service provider, and the data is then made available directly to them for purposes pursued by the service provider, this may as well be determined to be the controller.

Legal bases

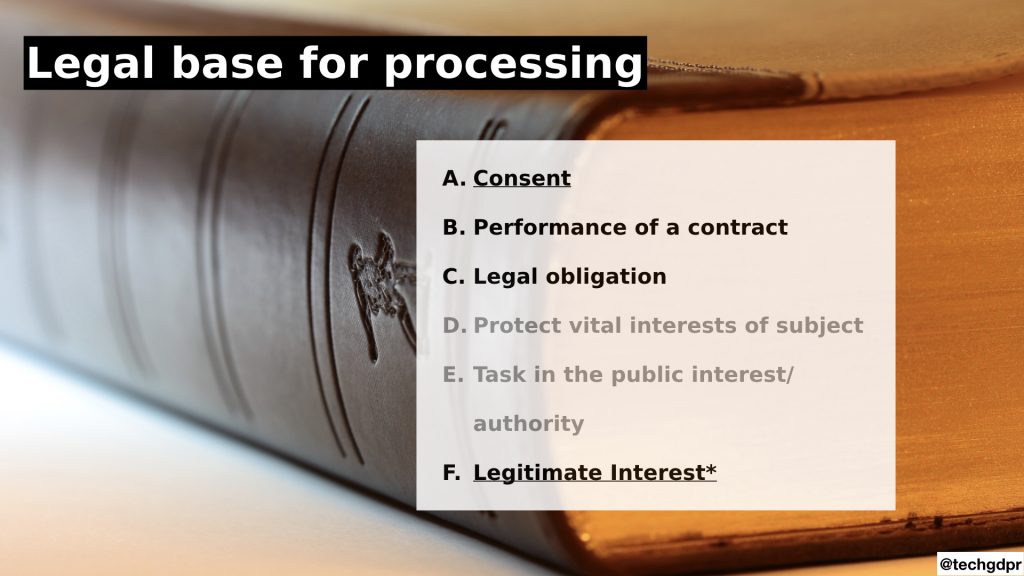

For the processing of personal data under the GDPR, the controller needs to define the legal base of processing. There are 6 possible legal bases (Art 6 GDPR, sub 1): (a) consent, (b) performance of a contract, (c) legal obligation, (d) vital interest, (e) public interest and (f) legitimate interest. Legal bases c, d and e do certainly not apply as WiFi-tracking can not be seen as a legal obligation, in anyone’s vital interest or in public interest in general. The other possible legal bases are analyzed hereunder.

Consent (Art 6.1a)

To claim the legal base of consent, the data subject will need to freely give prior consent to the processing in case. It is important to emphasize that consent need to be freely given and can therefor not be required for the provision or ‘payment with data’ of a service.

Recital 42: “… Consent should not be regarded as freely given if the data subject has no genuine or free choice or is unable to refuse or withdraw consent without detriment.”

Recital 43: “Consent is presumed not to be freely given if it does not allow separate consent to be given to different personal data processing operations despite it being appropriate in the individual case, or if the performance of a contract, including the provision of a service, is dependent on the consent despite such consent not being necessary for such performance.”

If consent was a precondition of a service, but the processing is not necessary for that service, consent is deemed to be invalid. Mixing in the consent for tracking with the use of guest WiFi or a loyalty program, is therefor not possible. Consent to WiFi-tracking should be given as an additional, non-required option.

In addition, consent should be revocable as easily as it has been given. A system should be in place that allows for consent to be revoked at any place and time.

Collecting consent

- Using a captive portal

- Using proximity push notifications

- Through a loyalty program

Performance of a Contract (Art 6.1b)

The performance of a contract may be used for fulfilling contractual obligations, as well as for the preparatory stages of concluding a contract. This however, would imply that at least at some point a ‘business’ relationship for the usage of data can be substantiated.

If data subjects may be rewarded in some kind of way for providing their tracking details and usage data, this could be a way to explore the use of Article 6.1b as a legal base, but not until the data subject has shown interest in such a relationship themselves, e.g. it can not be assumed. In short, for tracking behavior without further reward program, this legal base can not be applied.

Legitimate Interest (Art. 6.1f)

Legitimate interest may be the legal basis for processing user data if the interests of the user do not override the interest of the controller when considering the reasonable expectations of the data subject and their relationship with the controller, according to the GDPR. The determination of legitimate interest requires “careful assessment” of these reasonable expectations and the context of data collection.

A legitimate interest could be a purely commercial interest. The legitimate interest and it’s balancing against the interest of the data subject, need to be well documented and the essence of it is to be explained to the user.

What is important to consider for legitimate interest, is to analyze if there are less privacy-intrusive methods of reaching the same goal. If this is the goal, legitimate interest is unlikely to hold up.

Opinion 06/2014 on the notion of legitimate interests of the data controller under Article 7 of Directive 95/46/EC (which has been adopted as guidance under the GDPR) states:

The economic interests of business organizations to get to know their customers by tracking and monitoring their activities online and offline, should be balanced against the (fundamental) rights to privacy and the protection of personal data of these individuals and their interest not to be unduly monitored.

According to the same opinion, in case the goal of the tracking is marketing, there are more specific requirements under the ePrivacy Directive:

consent is required under Article 5(3) of the ePrivacy Directive for behavioral advertising based on tracking techniques such as cookies storing information in the terminal of the user.

Public space vs. private space

Strong opinions by data protection authorities, for example the Dutch DPA have been issued on WiFi-tracking in (semi-)public spaces. While WiFi-tracking within private (commercial) space can be legitimized, the moment personal data of those outside of the premises (e.g. passers-by) are analyzed it is very difficult to base this on legitimate interest.

If legitimate interest is used as a legal base, measures may need to be in place to ensure that only data subjects in the companies premises are being tracked.

Fulfilling the duty of information

Whichever legal base is chosen, as soon as personal data is collected of data subjects, they need to be informed. The regulation prescribes this as follows in Article 13:

Where personal data relating to a data subject are collected from the data subject, the controller shall, at the time when personal data are obtained, provide the data subject with all of the following information: …

This means that the controller has the duty to inform data subjects. Which is in the situation of an app or website, normally practiced by publishing a privacy notice. In the case of WiFi-tracking, this is obviously more problematic. One way may be to display a clear notice at the border of the perimeter, for example with a sticker on the door.

At the same time, data subjects should also have the choice not to be subjected to data processing, and would therefor need to be advised to switch off their WiFi in case they wish to opt out.

Data minimization and storage limitation

Whatever personal data is stored under the GDPR needs to be the minimum amount required to meet the specified purpose, and needs to be stored no longer than required for this purpose.

In current implementations of data protection for WiFi-tracking, there is a big emphasis on timely anonymization and limited storage as means to protect the privacy of the users. NS, in the example below, uses a different hash per day in order not to be able to correlate information across multiple days.

Mechanisms to exercise rights

Whenever personal data is collected from data subjects, they have rights under the GDPR, and they need to be informed about them and given ways to execute their rights. These rights could be rights to justification, right to erasure, right to information and the right not to object to automated decision making. The first ones could be surfaced through a website, portal or app of some sort. The last one needs to be closely considered in terms of what happens with their date.

Example of WiFi-tracking in practice and their explanation of compliance to the GDPR.

At the time of writing, Nederlandse Spoorwegen (Short:NS, translated: Dutch Railways) uses WiFi-tracking on (at the time of writing) 6 of its larger train stations. They make travelers aware of this with stickers indicating the use of WiFi-tracking around the station, and explain the mechanics behind it in their privacy policy: https://www.ns.nl/en/privacy/in-and-around-the-station.html

In summary, they use the legal base of the legitimate interest “to improve our services and to increase your safety in and around the station.” and use technical measures to limit and further pseudonymize the MAC addresses collected:

“The MAC address is immediately ‘hashed’ – converted into a series of characters. This series is then sent to a server, where we add extra random characters and hash the series again (a process known as ‘salt’). The extra characters differ per day, and are not stored on a computer. We then ‘cut out’ some of the characters, so that there is no way that the series can be traced to an individual.”

Other requirements under the GDPR

As WiFi-tracking counts as monitoring of behavior, and should in most cases be considered on large scale, both the controller and processor will need to designate a data protection officer, and, in case it has no establishment in the EU, also designate a EU representative.

ePrivacy Regulation and Directive

The ePrivacy directive, and in the future the ePrivacy Regulation deals with communication instead of data processing, and is therefore relevant for the use of WiFi-tracking. It will be further scrutinized with the introduction of the ePrivacy regulation. The regulation prohibits companies from using consent collection methods that force users to agree to tracking in order to receive access to services. The Regulation provides three possible purposes for tracking:

- When it is necessary to transmit an electronic communication.

- When it is necessary to provide an information society service requested by the user.

- When it is necessary to measure the reach of an information service requested by the user.

The original draft of the ePrivacy Regulation also contains provisions for the protection of data subjects using public WiFi. That initial draft stated that tracking an individual’s location through a WiFi or Bluetooth connection was permitted. However, in response, Parliament and the Working Party proposed solutions that would require businesses that have locations which provide WiFi to obtain a data subject’s consent before tracking and to post a notice on the possible dangers of using their WiFi connection in a prominent place.

The latest draft of the ePrivacy regulation, dated October 2018, contains the following relevant passage in recital 25:

A single wireless base station (i.e. a transmitter and receiver), such as a wireless access point, has a specific range within which such information may be captured. Service providers have emerged who offer physical movements’ tracking services based on the scanning of equipment related information with diverse functionalities, including people counting, such as providing data on the number of people waiting in line, ascertaining the number of people in a specific area, etc referred to as statistical counting for which the consent of end-users is not needed, provided that such counting is limited in time and space to the extent necessary for this purpose.

Providers should also apply appropriate technical and organisations measures to ensure the level if security appropriate to the risks, including pseudonymisation of the data and making it anonymous or erase it as soon it is not longer needed for this purpose. Providers engaged in such practices should display prominent notices located on the edge of the area of coverage informing end-users prior to entering the defined area that the technology is in operation within a given perimeter, the purpose of the tracking, the person responsible for it and the existence of any measure the end-user of the terminal equipment can take to minimize or stop the collection.

Additional information should be provided where personal data are collected pursuant to Article 13 of Regulation (EU) 2016/679. This information may be used for more intrusive purposes, which should not be considered statistical counting, such as to send commercial messages to end-users, for example when they enter stores, with personalized offers locations, subject to the conditions laid down in this Regulation, as well as the tracking of individuals over time, including repeated visits to specified locations.

There is no final draft of the ePrivacy Regulation yet, so the exact implementation of these requirements remains unclear for the time being. It is expected that once officially adopted, the Regulation will come into force 24 months later.

Conclusion

Generally spoken, WiFi-tracking under the GDPR (and ePrivacy regulation in the future) is challenging. The main problems revolve around:

- WiFi-tracking relies on MAC addresses, which are considered personal data, even in hashed form.

- It is required to inform data subjects before collection of personal data takes place.

- Consent as a legal base is challenging as it’s very difficult to collect valid, freely given consent from data subjects. Where consent may be collected, e.g. through a captive portal, it is quite unlikely to have a high conversion rate.

Possible approaches to GDPR compliance

There are some approaches that can be considered to utilize WiFi-tracking within the requirements of the GDPR:

1. Informing and asking for consent through a captive portal, push notification or app before tracking users.

Where the legal base of processing personal data would be consent, one approach may be to ask consent through a captive portal. This could be set up as an additional option when asking people to agree to conditions for using guest WiFi.

2. Relying on legitimate interest for tracking.

It seems possible to rely on legitimate interest for tracking in certain cases, but this limits what the tracked data can be used for. It needs to be possible to argue for a real, legitimate interest that can not or hardly be met using less privacy-intrusive methods. It can be further debated if direct marketing or advertising can constitute a legitimate interest for this purpose or not. If that is the case, all data subjects need to be given an easy way to opt-out of this tracking.

3. Find a way to moving the data out of scope of the GDPR though anonymized collection.

If a way can be found to properly anonymize data following the requirements of the GDPR, it will be out of scope of the GDPR and can therefor (from that point onwards) be processed freely. The challenge with this approach is the correlation of data which will become impossible if the data is anonymized right at collection. Also, for low traffic areas, the sample size may be too insignificant to ensure that tracking is truly anonymous.

NOTE: This article does not constitute or replace legal and professional advise. Consult your lawyer or privacy professional before using WiFi-tracking.