There have been many discussions about the big problem of the right to be forgotten (right to erasure, Article 17) under the GDPR. As blockchain generally is immutable, and the GDPR requires personal data to be deleted. Many people therefor conclude that it is impossible to store any kind of personal data on a blockchain.

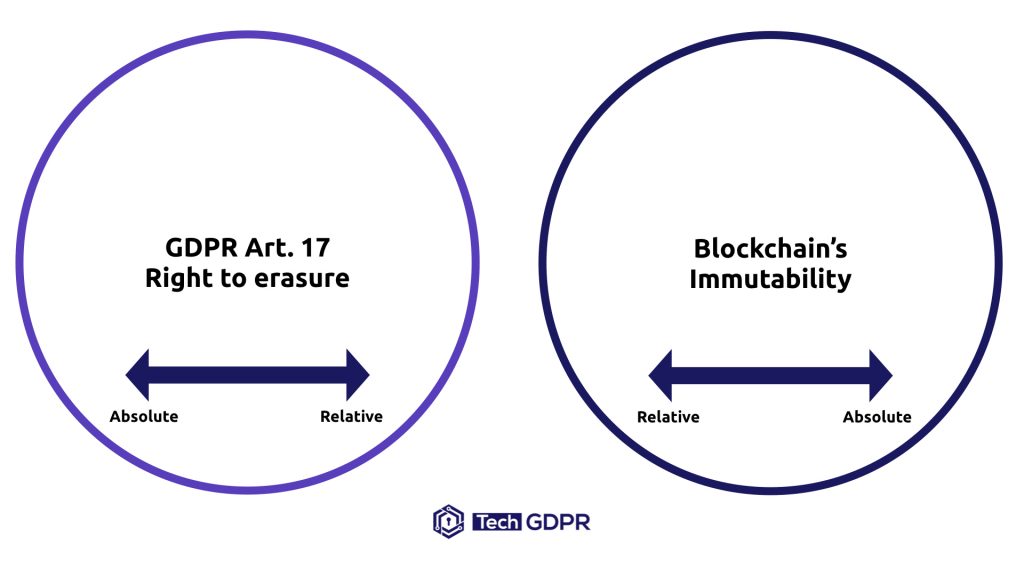

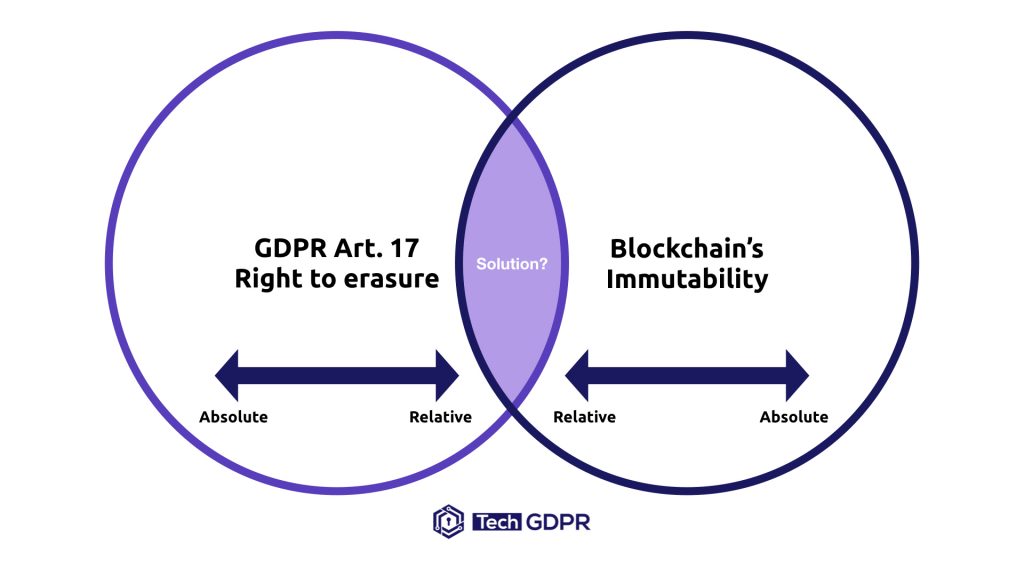

In my opinion, however, this needs to be seen with more nuance, and as lawyers like to say, it all depends on the specific circumstances; blockchain is not always strictly immutable, the right to be forgotten is not absolute, and the definition of personal data is still not 100% clear. If you look past the headlines and dive into the details, you will see this situation is not that black and white.

1. Blockchain is not always strictly immutable

Already in the very first paper on blockchain, “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System” by Satoshi Nakamoto, there was the notion of pruning: “Once the latest transaction in a coin is buried under enough blocks, the spent transactions before it can be discarded to save disk space.” Meaning even in the first-generation protocol of Bitcoin, there is a technical method to delete certain data from the chain. So far, this has not been implemented, but there is a methodology to achieve this without breaking the system. Obviously in this particular way, a node operator could still choose to maintain all data that ever comes across, so in practice this may not with with Bitcoin unless additional safeguards to guarantee this are being put in place.

With later-generation protocols, such as with EOSIO, there is more sophisticated governance in place. By designating certain block producers who could, based on a constitution, agree to remove certain data, or mutually agree to block access to certain data for the outside. Even though this may limit transparency and centralizes some of the decision making, this may still be a feasible solution for certain use cases. For example Europechain aims at setting up networks with only EU/EEA block producers that are all under a Data Protection Agreement (DPA), specifically to offer a GDPR compliant way in which blockchain can be used while keeping most of the advantages of using blockchain in place.

Immutability can for certain purposes be very valuable, but for Personal Data it may not be ideal.

2. The right to be forgotten is not absolute

The right to be forgotten if often cited as the holy grail of protection your personal data, but it can not always be applied. According to Article 17, it can for example be used under the following circumstances:

- Personal data is no longer needed for the purpose, for example, if it was processed for the provision of a contract (Article 6.1(b)), but the contract has been cancelled or has expired.

- It was processed under consent (Article 6.1(a)), and the consent has been withdrawn.

- It has been processed under legitimate interest, but the legitimate interest has been challenged and no overriding interests prevail.

- The processing was unlawful in the first place.

The right to be forgotten does for example not apply if the processing is (still) necessary for the performance of a contract, for scientific or historical reasons in the public interest, to comply with a legal obligation, or if the legitimate interest continues to overrule the interest of the data subject.

If a controller has made personal data public, and publishing on a public blockchain should be seen as making public, they are required to inform others who are processing the data that is should be deleted. It’s an interesting question how that should work in a distributed environment with public actors, but this is not impossible.

3. The definition of personal data is still not 100% clear

In blockchain environments clearly readably personal data should not be used. In particular within public permissionless blockchains there is no good reason to do so. Most projects resort to storing hashes of information or transactions on-chain to prove certain things off-chain. Depending on the circumstances, such hashes could be considered pseudonymous or anonymous. Pseudonymous data is still in-scope of the GDPR, and should therefor adhere to it, anonymous data is out of scope. What exactly is to be considered pseudonymised following a specific approach, and therefor in scope of the GDPR, was previously (before the GDPR) explained in Opinion 2014/05 of the Working Party 29 (WP216). However, this has not been formally adopted by the EDPB. This makes it a lot harder to establish if, for example hashed information is pseudonymous or anonymous from the perspective of the GDPR.

Is the right to be forgotten in blockchain really a problem?

Well yes. Very often, there are certainly potential problems with storing pseudonimysed personal data in a blockchain, however one should be looking at the particular circumstances: which source-data is pseudonimised, encrypted or hashed, where is it stored, and can it be related to other on-chain events, what happens if you delete the source-data, and how strong is the entropy?

To find solutions for this challenge, it is important to consider both the technical (immutability) and the legal (how absolute is the right to erasure?) aspects, and the overall situation. It will stand or fall with the small details, and because the GDPR is a new regulation and blockchain a new technology, it will always be a risky undertaking to deploy this ‘in the wild’.

The only way in which this challenge can be approached, is through Privacy by Design: ensuring all privacy controls are implemented right from the start, and making sure products, protocols and their apps and UX are designed in a privacy friendly way. Launching an immutable system with privacy weaknesses that are not fully thought through, and documented, is quite clearly a violation against Article 25 of the GDPR on Data Protection by Design and by Default.