Today, I had the opportunity to present the key issues of Blockchain & DLT under the GDPR to a delegation of the European Commission in Berlin. Below is a summarised version of the issues I presented.

1. Is the Opinion 05/2014 by Working Party 29 still valid?

Article 29 Working Party issued comprehensive guidance on Anonymisation Techniques in April 2014 (WP216), setting a high standard for the requirements of true anonymisation, and specifies what is to be interpreted as pseudonymisation – which is merely a method to reduce linkability of a dataset with the original identity of a data subject.

Many applications of DLT requires some verification data to be stored on-chain, which, depending on interpretation and the specific requirements can be seen as anonymous or pseudonymous.

During its first plenary meeting on May 25th, 2018 the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) endorsed a number of GDPR related WP29 Guidelines, but not “Opinion 05/2014 on Anonymization Techniques” by “Art. 29 Working Party”.

The EDPB should clarify whether this opinion by WP29 may be used as a guideline, or ideally issue new guidelines that allow for sufficiently protected pseudonymous data and verification hashes to be recognised as anonymous.

2. Clarification of distribution of responsibilities in a decentralised environment (DLT) according to given roles under GDPR.

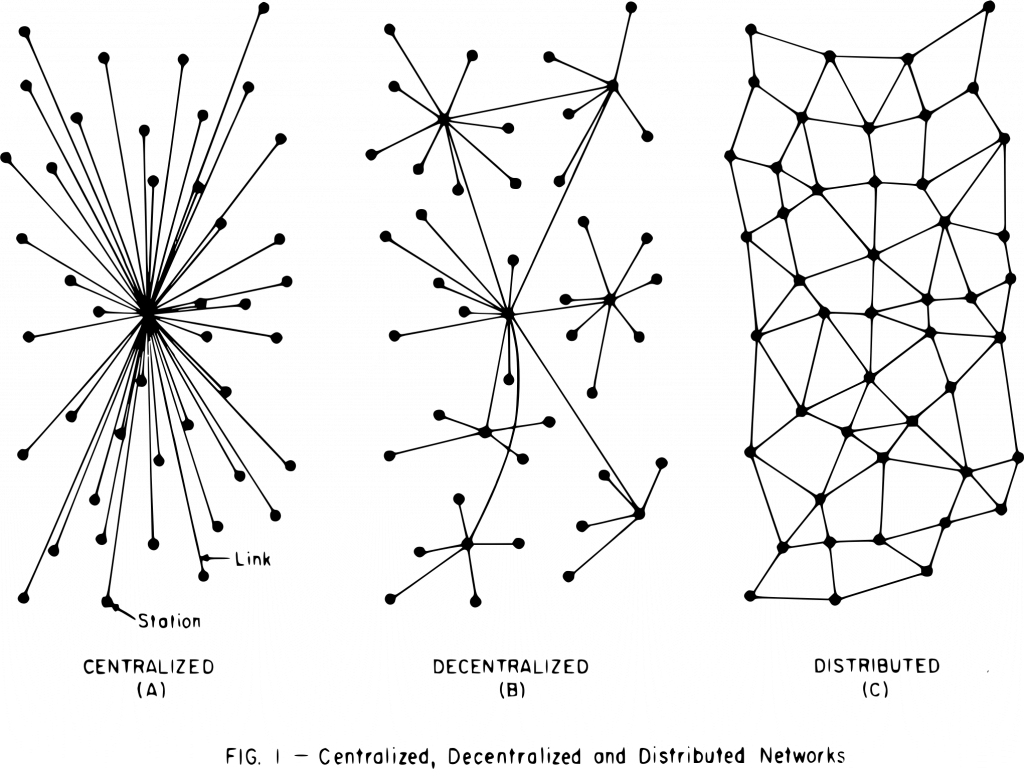

The architecture (or topology) of systems using DLT is vastly different from more traditional systems comprising of a client-server, or client-cloud architecture. The GDPR is clearly designed for a client-server architecture, with clear distinguishable rights and duties between a data controller, who is primarily responsible, a data processor, who processes data on behalf of a controller, and a data subject, of whom the personal data is being processed.

This is not translatable into blockchain or distributed ledger technology, where every node could play every role, not overseen by a central entity or system. Participants may have different roles under different circumstances, and may have multiple roles at the same time. In addition, the requirement of concluding a Data Processing Agreement in a public permissionless network is very difficult to fulfil, and other overarching measures may be required.

Clarification of the GDPR roles of the different actors within the blockchain ecosystem, under different circumstances is highly desirable to give innovators enough legal certainty to continue their efforts.

3. Clarification regarding deletion and rectification obligations under DLT.

Under Article 16 and 17 of the GDPR, data subjects have the right to have incorrect personal data corrected, and have their personal data that is no longer required erased.

This poses a problem when using DLT, that primarily derives its trust from its immutability. Because data, including personal data on DLT can not be rectified or erased, and many blockchains are public, the best practice so far is to not directly store personal data on a blockchain but only a verification value, also known as a hash, of some kind. However, as highlighted before, there is no current valid guidance on exact limits of anonymisation, so how this is to be applied remains unclear.

Technical approaches to resolve this problem exist, for example through the ability of nodes to restrict access to certain information, to only allow ‘keyed hashes’, which all have a unique key stored off-chain that can be deleted, or by using a mutable implementation of DLT, which unfortunately hardly ever helps us trust the technology as it relies on a trusted third party and should not be seen as a true solution. Which defeats the appeal of blockchain and DLT.

Within current practices using data backups in more traditional settings, it can also not be assumed that all personal data is effectively deleted, in particular from offline tape backups. It can also be questioned what the technically implementation of ‘deleting data’ in a traditional sense is: under most circumstances this is just ‘unlinking’ data, which can still be recovered.

Further guidance, and more flexibility on the interpretation of deletion and rectification obligations, in particular in a blockchain environment, is requested.

4. Request to ensure future guidance takes the different blockchain and DLT architectures into account.

When the EDPB or other regulators are providing guidance on blockchain under the GDPR, it is essential to understand and consider the different blockchain architectures currently available, and possibly those of the future. A public permissionless blockchain, free to join, participate in and download for everyone, is vastly different from a private permissioned one, related technologies that are technically not blockchain but still fall within the scope of distributed ledger technologies, such as Tangle and Hashgraph, have yet another very different architecture requiring a different approach.

We’d like to urge the regulators and in particular the EDPB to take these fundamental differences into account when issuing further guidance.