This issue highlights a couple of analyses that perhaps help to understand the essence of AI and other new technology, to which the GDPR applies, and the urgent need for digital self-determination for its users.

Self-determination and AI

Digital self-determination of a user: The Swiss Federal Data Protection Commissioner FDPIC stresses that the current data protection legislation is directly applicable to AI used in the economic and social life of the country. In particular, the Data Protection Act in force since 1 September is directly applicable to all AI-based data processing. To this end, the FDPIC reminds manufacturers, providers and operators of such applications of the legal obligation to ensure that the data subjects have as much digital self-determination as possible when developing new technologies and planning their use:

- the user has the right to know whether they are talking or writing to a machine,

- whether the data they have entered into the system is further processed to improve the machine’s self-learning programs or for other purposes, and

- to object to automated data processing or to demand that automated individual decisions be controlled by a human being.

The law also requires a data protection impact assessment in the event of high risks. On the other hand, the use of large-scale real-time facial recognition or global surveillance and assessment of individuals’ lifestyles, otherwise known as “social scoring”, is prohibited.

Legal processes

The Data Act: On 9 November, the European Parliament adopted the text of the European Data Act. Next, it must be approved by the Council. The act makes more data available for use and sets up rules on who can use and access what data for which purposes across all economic sectors in the EU. This law applies to:

- the manufacturers, suppliers and users of products and related services placed on the market in the Union;

- data holders that make data available to data recipients in the Union;

- data recipients in the Union to whom data are made available;

- public sector bodies that request data holders to make it available for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest and the data holders that provide data in response to such a request;

- providers of data processing services offering such services to customers in the Union.

According to the updated text, to promote the interoperability of tools for the automated execution of data-sharing agreements, it is necessary to lay down essential requirements for smart contracts which professionals create for others or integrate into applications.

FISA 702: Meanwhile, the US Congress unveils the Government Surveillance Reform Act. The bill reauthorizes Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act for four more years, allowing intelligence agencies to continue to use the powers granted by that law, but with new protections against documented abuses and new accountability measures. For instance, it prevents warrantless searches, ensures foreigners are not targeted for spying on Americans they communicate with and prevents the collection of domestic communications. It also includes a host of reforms to government surveillance authorities beyond Section 702, including requiring warrants for government purchases of private data from data brokers.

EDPB documents

Tracking tools: The EDPB addresses the applicability of Art. 5(3) of the ePrivacy Directive to different tracking solutions. The advent of new tracking technologies to both replace existing tracking tools (due to the discontinuation of third-party cookie support) and generate new business models has emerged as a key data protection problem. The recommendations define four main elements: “information,” “terminal equipment of a subscriber or user,” “gaining access,” and “stored information and storage.” A partial list of use cases includes a) URL and pixel tracking, b) local processing, c) IP-only tracking, d) intermittent and mediated IoT reporting, and e) unique identifier.

Official guidance

Synthetic data: Synthetic data could function as a privacy-enhanced technology, as it allows the application of data protection by design. This synthesis can be performed using sequence modelling, simulated data, decision trees or deep learning algorithms. Creating synthetic data from real personal data would itself be a processing activity subject to the GDPR. It is therefore necessary to consider the regulatory provisions, in particular, the principle of proactive responsibility and the assessment of a possible re-identification risk. In some cases, data sets may be too complex to obtain a correct understanding of their structure or it may be difficult to mimic outliers from real data, undermining analytical value for specific use cases. In such situations, alternative or complementary PETs should be used, such as anonymisation and pseudonymisation.

Health apps: German data protection body DSK has published a position paper on cloud-based health applications (in German). Since 2020, the Digital Health Applications Ordinance has regulated certain digital health applications to ensure the legal requirements for data protection and data security. However, several other health applications are not covered by these regulations. Thus, the following must be taken into account when using a wide range of health apps:

- Data processing roles must be clearly defined in each case. Manufacturers, doctors and other medical service providers as well as cloud services come into consideration.

- The use of application with a privacy-friendly design without the cloud functions and possibly without linking to a user account.

- The app manufacturers or operators must fulfil the rights of data subjects to information, correction, deletion, restriction of processing and data portability.

- The processing must be limited to the necessary extent, and be compatible with the purpose of the application.

- A data protection legal basis is required for the use of personal data for research purposes.

More from supervisory authorities

Chatbots: The data protection authority of Liechtenstein explains the essence of chatbots – a software-based dialogue system that enables text or voice-based communication. From a technical perspective, there are different types of chatbots, ranging from simple rule-based systems to artificial intelligence AI systems. European data protection authorities are currently dealing with the issue of whether AI-based solutions meet the requirements of data protection law. At the same time, chatbot systems are often offered as cloud services, where GDPR rules will always apply, (legal basis, information obligation, handling of cookies, storage of chatbot data, processing of sensitive data, and data reuse).

Similarly, the Hamburg Data Protection Commissioner offers a checklist for the use of LLM-based chatbots, (in English). Recommended steps would include internal regulations for employees, involvement of a data protection officer, creation of an organisation-owned account, and no transmission of any personal data to the AI. Overall, the results of a chatbot request should be treated with caution. You can also reject the use of your data for training purposes, and opt-out of saving previous entries.

Explainable AI: A transparent AI system provides insight into how AI systems process data and arrive at their conclusions, providing an understanding of the “reasoning” that led to the conclusions/decisions, explains the EDPS. Greater accountability will lead to a better assessment of the risks that data controllers need to carry out. At the same time, many efforts to improve the explainability of AI systems often lead to explanations that are primarily tailored to the AI researchers themselves, rather than effectively addressing the needs of the intended users. Read the deep dive into the risks of opaque AI systems here.

Enforcement decisions

Simplified procedures: The French privacy regulator CNIL has issued ten new decisions under its new simplified sanction procedure, introduced in 2022. Some cases focus on geolocation and continuous video surveillance of employees. The CNIL pointed out that the continuous recording of geolocation data, with no possibility for employees to stop or suspend the system during break times, is an excessive infringement of employees’ right to privacy unless there is special justification. Similarly, the prevention of accidents in the workplace does not justify the implementation of continuous video surveillance of workstations and is neither appropriate nor relevant.

Telemarketing: The Italian data protection authority has imposed a fine of 70,000 euros on a coffee-producing company for promoting its brand through unwanted phone calls. Furthermore, the purchase order was considered as proof of consent to marketing. Users’ data was acquired in various ways: through the form on the website, through word of mouth from customers, and through contact lists collected by third-party companies, without having acquired the consent of the users. The company will now have to delete data acquired illicitly and activate suitable control measures so that the processing of users’ data occurs in compliance with privacy legislation throughout the entire supply chain.

Similarly, the Czech data protection authority imposed a fine of approx. 326,000 euros for sending commercial communications in favour of third parties. Since 2015, a transport company distributed commercial messages for the benefit of third parties to the email addresses of its customers, without obtaining the prior consent of the recipients, and without the possibility of rejecting these commercial communications in any way. It should be emphasized that the company did not offer its products or services, so it was not entitled to use the so-called “customer exception”, (to offer similar products or services).

Data breaches

Processor’s obligations: The Danish Data Protection Authority has expressed criticism in a case where a data processor, Mindworking, had not ensured adequate security when developing a web application that was targeted at real estate agents. In particular, it was not secured against unauthorised persons inspecting the source code and thus being able to access personal data on the platform, (linked to a specific property that was for sale). The information could be accessed by users after they had logged in with a username and password. The user could access the information by pressing a function key and activating so-called “Dev tools”. The regulator concluded that the data processor should have carried out relevant tests of the platform before commissioning it, (Art. 32 of the GDPR).

Data security

Data breach: Finland’s data protection authority reminds organizations that they must assess the seriousness of a data security breach from the point of view of the data subjects. As a rule, the data controller must notify the authority if the breach may cause a risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons, (even if all the information about the incident is not yet completely clear), within 72 hours. Thus, the controller must accurately assess the seriousness of the possible effects on the data subjects affected by the violation. The purpose is to assess the seriousness of the effects on the data subjects, not the consequences on the controller. Data subjects also must be notified of a high-risk situation without undue delay, (even if the high risk is eliminated by measures taken after the breach).

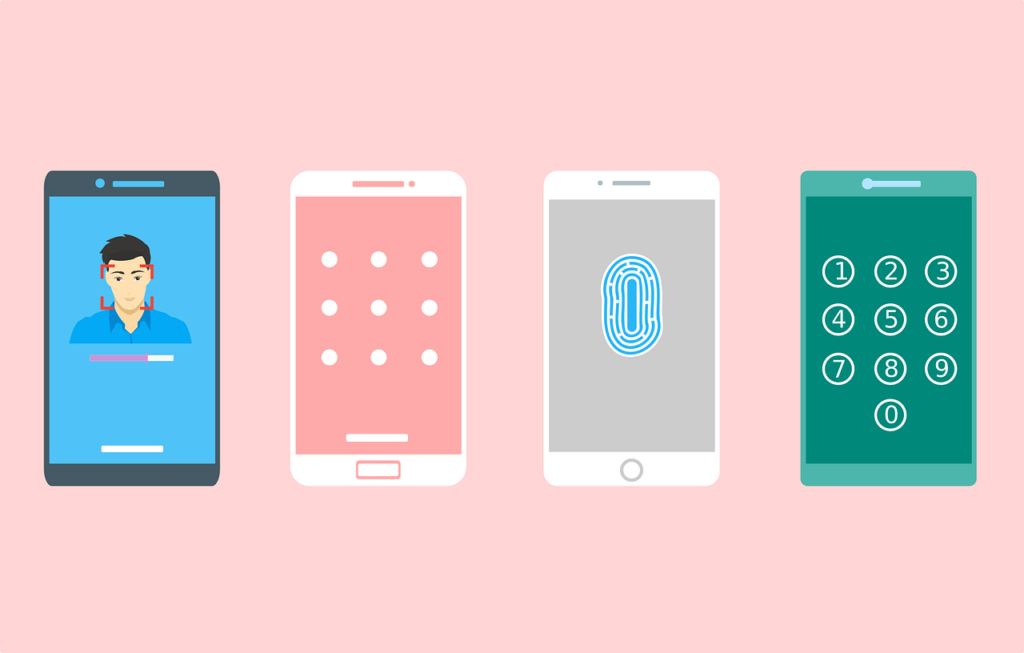

Password dilemma: Almost everyone uses bad passwords, often unconsciously, states the Dutch data protection authority. The standard password requirements of 8 characters with enforced punctuation and numbers encourage this. These lead to short passwords full of human patterns. People are also very predictable if they try to use long passwords. Instead of something completely random, they quickly choose a year, their favourite sports team or another simple adjustment, such as starting with a capital letter. It is therefore recommended to use long passwords, which are so random that a hacker must try all options to retrieve the password, which are slower, and hence less profitable.

Big Data

DSA and minors’ safety: The European Commission has sent Meta and Snap requests for information under the Digital Services Act, following their designation as Very Large Online Platforms. Companies have until 1 December to provide more information on risk assessments and mitigation measures to protect minors online, in particular about the risks to mental health and physical health, and on the use of their services by minors. Under Art. 74 of the DSA, the Commission can impose fines for incorrect, incomplete, or misleading information in response to a request for information.

Medical research data reuse: Sensitive health information donated for medical research by half a million UK citizens has been allegedly shared with insurance companies for years according to The Guardian. An investigation found that data was provided to insurance consultancy and tech firms for projects to create digital tools that help insurers predict a person’s risk of getting a chronic disease. UK Biobank, set up in 2002 and described as a ‘crown jewel’ of British science, claims that it only allows access to bona fide researchers for health-related projects in the public interest, whether employed by academic, charitable, or commercial organisations and that participants were promptly informed. Read the full analysis here.